We are currently experiencing a renaissance in the scientific study of magic, and my background in stage magic provides me with a unique perspective on this fruitful research area. This page highlights some of the directions in which my research on this topic is headed:

The "Invisible Gorilla" of Simons and Chabris (1999, Perception) is a compelling demonstration of attentional filtering, but it is rather rare to attend a basketball game and miss a gorilla walking across the court. On the other hand, it is not rare to attend a magic show and miss a host of salient events that happen right in front of your eyes. Thus, magic provides an ecologically valid means of examining the phenomenon of inattentional blindness.

To this end, I have developed a magic trick for use in studying inattentional blindness in (and out of) the laboratory. Importantly, the magic trick allows for control over many of the variables that were manipulated in the early inattentional blindness research carried out by Mack & Rock (1998). For the first time, a re-examination of Mack & Rock's findings can be carried out under the umbrella of a single methodology that has high ecological validity.

Barnhart, A. S. & Goldinger, S. D. (2014). Blinded by magic: Eye-movements reveal the misdirection of attention. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1461. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01461 (open access)

In a series of follow-up experiments, we observed that microsaccade dynamics are predictive of whether a person will succeed or fail on a task like this one. These tiny movements of the eye effectively point to where a person's covert attention is placed.

Barnhart, A. S., Costela, F. M., Martinez-Conde, S., Macknik, S. L., & Goldinger, S. D. (2019). Microsaccades reflect the dynamics of misdirected attention in magic. Journal of Eye Movement Research, 12(6). https://doi.org/10.16910/jemr.12.6.7 (open access)

To this end, I have developed a magic trick for use in studying inattentional blindness in (and out of) the laboratory. Importantly, the magic trick allows for control over many of the variables that were manipulated in the early inattentional blindness research carried out by Mack & Rock (1998). For the first time, a re-examination of Mack & Rock's findings can be carried out under the umbrella of a single methodology that has high ecological validity.

Barnhart, A. S. & Goldinger, S. D. (2014). Blinded by magic: Eye-movements reveal the misdirection of attention. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1461. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01461 (open access)

In a series of follow-up experiments, we observed that microsaccade dynamics are predictive of whether a person will succeed or fail on a task like this one. These tiny movements of the eye effectively point to where a person's covert attention is placed.

Barnhart, A. S., Costela, F. M., Martinez-Conde, S., Macknik, S. L., & Goldinger, S. D. (2019). Microsaccades reflect the dynamics of misdirected attention in magic. Journal of Eye Movement Research, 12(6). https://doi.org/10.16910/jemr.12.6.7 (open access)

Analogies can be useful for guiding research and theory, but they can also constrain thinking in ways that limit theory development. Within psychology and neuroscience, widespread use of the spotlight analogy has led to a conceptualization of attention that is biased toward the visuo-spatial domain at the expense of temporal and internal dimensions. The same bias is prevalent among magicians, who also tend to describe attention using the spotlight analogy.

However, on some level, magicians have awareness that attention can be influenced by variables outside of the visuo-spatial domain. They regularly teach that sleight of hand should occur on the “off-beat” in order to evade detection. Embedded in this idea are a few assumptions. The first of these is that attention is not a static entity. Timing a sleight to occur at a specific moment in time rather than focusing on diverting attention in space suggests that magicians understand attention to be a dynamic process that waxes and wanes in time. Secondly, framing the momentary attentional suppression as a “beat” implies that the waxing and waning of attention follows a predictable, regular time course, like the beats of a metronome. While these intuitions do not fit comfortably into many popular models of attention, they are in line with modern dynamic models of attention which tend to focus on temporal over spatial aspects of attention. Thus, temporal attention is an area of study where both science and magic can benefit from an interdisciplinary collaboration.

In our first published work on this topic, we showed that a visual event is less likely to be detected if it happens out of phase with an irrelevant, auditory rhythm, but that this effect varies across frequencies.

Barnhart, A. S., Ehlert, M. J., Goldinger, S. D., & Mackey, A. D. (2018). Cross-modal attentional entrainment: Insights from magicians. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 80, 1240-1249. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-018-1497-8 (pdf)

However, on some level, magicians have awareness that attention can be influenced by variables outside of the visuo-spatial domain. They regularly teach that sleight of hand should occur on the “off-beat” in order to evade detection. Embedded in this idea are a few assumptions. The first of these is that attention is not a static entity. Timing a sleight to occur at a specific moment in time rather than focusing on diverting attention in space suggests that magicians understand attention to be a dynamic process that waxes and wanes in time. Secondly, framing the momentary attentional suppression as a “beat” implies that the waxing and waning of attention follows a predictable, regular time course, like the beats of a metronome. While these intuitions do not fit comfortably into many popular models of attention, they are in line with modern dynamic models of attention which tend to focus on temporal over spatial aspects of attention. Thus, temporal attention is an area of study where both science and magic can benefit from an interdisciplinary collaboration.

In our first published work on this topic, we showed that a visual event is less likely to be detected if it happens out of phase with an irrelevant, auditory rhythm, but that this effect varies across frequencies.

Barnhart, A. S., Ehlert, M. J., Goldinger, S. D., & Mackey, A. D. (2018). Cross-modal attentional entrainment: Insights from magicians. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 80, 1240-1249. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-018-1497-8 (pdf)

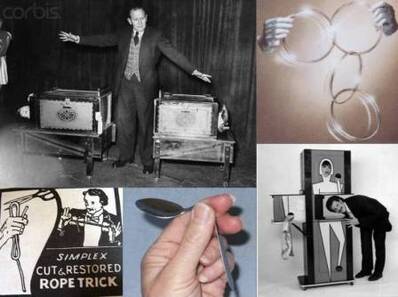

Most magic tricks rely heavily on perceptual and cognitive biases. In fact, much of the deception in a magic show is self-deception on the part of the audience members. Magicians simply create situations that allow audience members to generate implicit assumptions which turn out to be invalid; they pave the garden path down which audience members are more than happy to stroll. Framed another way, a magic show can be thought of as a series of ambiguous events. The magician’s goal is to nudge the audience toward an interpretation of each ambiguous event that differs from the optimal resolution. When presented with a distorted or ambiguous input, application of Gestalt principles can facilitate disambiguation, but it can also lead to faulty disambiguation in cases where the true interpretation is improbable. In my first publication on the psychology of magic, I argued that the Gestalt grouping principle of good continuation is among the most exploited psychological tendencies in magic.

Barnhart, A. S. (2010). The exploitation of Gestalt principles by magicians. Perception, 39, 1286-1289. https://doi.org/10.1068/p6766 (pdf)

Barnhart, A. S. (2010). The exploitation of Gestalt principles by magicians. Perception, 39, 1286-1289. https://doi.org/10.1068/p6766 (pdf)

Magicians frequently rehearse their sleight of hand before a mirror in order to gain the perspective of their audience. However, magic instructors often warn that this practice can lead to self-deception, as many novice magicians unconsciously blink their eyes when engaging in deceptive action, thereby blinding themselves to evidence of their proficiency. There are few concrete examples of self-deception in the literature that provide definitive evidence in support of deep self-deception, where a person both knows the truth and pushes that truth outside their consciousness.

We attempted to elicit magicians’ blinking behavior under well-controlled laboratory conditions and to identify variables that impact a performer’s tendency to engage in it. We invited magicians to learn a difficult set of coin magic sleights over the course of a week and to perform the routine in a rehearsal setting (with a mirror) and a performance setting (without a mirror). We quantified blink rates in the videos of these performances. Indeed, magicians were more likely to blink when engaging in deceptive action than when not, and blinking was more prevalent when performing more difficult sleights. However, this tactical blinking was only evident in the performance setting.

We suggest that rather than serving as self-deception, tactical blinking may enhance deception of the audience through encouragement of synchronized blinking in spectators. Alternatively, self-deception may emerge later in the learning process, after some basic motor proficiency has been established.

Barnhart, A. S., Richardson, K., & Eric, S. (2022). Tactical blinking in magicians: A tool for self- and other-deception. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, 9(3), 257-266. https://doi.org/10.1037/cns0000321 (pdf)

We presented on this work at the 2022 meeting of the Science of Magic Association. Video from that presentations appears below.